The Curse Between Us: An Analysis on ἀγάπη Between Jujutsu Kaisen’s Gojo & Geto

Suguru Geto (left) laughing with Saturo Gojo (right).

The relationship between Satoru Gojo and Suguru Geto in Jujutsu Kaisen resists simplification. It is not merely the camaraderie of fellow sorcerers nor a clean arc of hero and fallen antagonist. Rather, it is a deeply woven narrative of existential togetherness, a bond whose rupture sends shockwaves through their respective identities. Their relationship—whether interpreted as intense friendship or veiled romance—exemplifies the paradox of being the strongest only in shared presence. The narrative suggests that their power, ideology, and identity are inextricably tethered to each other, and that without that tether, they are fundamentally incomplete. This essay explores their bond through philosophical and psychological lenses, drawing from thinkers like Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Jacques Lacan, and Martin Heidegger, as well as the symbolic language of the anime itself.

Diverging Ideologies: The Flip of the Moral Axis

In the beginning of their story, Gojo and Geto represent two contrasting views on the nature of strength and moral duty. Gojo's early nihilism—"Why protect the weak? They are going to die anyway"—reflects an embryonic Nietzschean will to power. He embodies the Ubermensch, standing above traditional morality, questioning whether compassion toward the weak is necessary or merely performative. In contrast, Geto starts as the moral idealist, driven by a deep sense of responsibility to protect those who cannot protect themselves. He is akin to Kierkegaard's Knight of Faith, acting out of duty and belief, grounded in ethical concern.

Geto arguing with Gojo.

But with the death of their friend, Riko Amanai, the moral axis flips. Gojo's near-death experience and failure to protect her catalyze a transformation. Having unlocked his Limitless Cursed Technique and Reverse Cursed Energy, he becomes the apex of power, but his emotional world is no longer centered on himself. He begins to believe in the importance of protection—not merely as a function of power but as a purpose for it. Geto, on the other hand, descends into despair. The world he fought to protect is what allowed Riko to die. He begins to see the weak not as those in need of protection but as the source of corruption itself. In Kierkegaardian terms, Geto becomes the Knight of Infinite Resignation, losing faith not just in the world but in himself.

This inversion of perspectives is not just a moral shift; it is an ontological crisis. Their selfhoods were scaffolded in relationship to each other. Without that shared project, their identities destabilize. Heidegger's notion of "being-with" (Mitsein) is helpful here: our existence is always already entangled with others. For Gojo and Geto, their very understanding of strength and responsibility is entangled in their shared past.

Blue as Gravity: The Symbolic Power of Togetherness

The anime's "Hidden Inventory Arc" introduces the opening song "Where Our Blue Is," a poetic meditation on longing, separation, and persistent emotional resonance. The use of "blue" is not incidental. In the metaphysics of Jujutsu Kaisen, Gojo's technique involves two core abilities: Red (repulsion) and Blue (attraction), both gravitational manipulations of matter. Blue draws things toward itself, much like Gojo's own subconscious desire for relational proximity, even if veiled by sarcasm and stoicism.

Gojo swirling in the wind: falling and levitating with the use of his curse technique, Blue.

The lyrics reinforce this emotional gravity:

"Even if I find out that your scent is different from mine / At the bottom of eternity, where I left behind / Blue still lives there."

Here, "eternity" recalls Gojo's Infinity technique, a literal barrier between himself and others. Yet, paradoxically, it is at the "bottom of eternity" where blue—their connection—still resides. This line resonates with Lacan's idea of desire as "the desire of the Other." Gojo's Infinite space isn't just a defense mechanism; it is also a metaphor for the unreachable distance between self and Other. His desire to reach Geto persists precisely because it is no longer reciprocated.

The lyric, "The words that curse you are stuck in my throat," may symbolize the unspeakable pain of Geto's transformation. This image aligns with Geto's curse technique—the swallowing of curses—and suggests a mutual entanglement of guilt, love, and suppressed rage. Their separation is not one of indifference, but of unuttered despair.

The Slowing Fish: Akari and the Symbolism of Estrangement

The third ending of Jujutsu Kaisen, titled "Akari," serves as a visual metaphor for their mutual misunderstanding. In this scene, Geto watches a white fish (symbolizing Gojo) swim toward him. But as he averts his gaze, the fish slows. Here, Geto believes Gojo is accelerating away in strength, power, and relevance—leaving him behind. Yet Gojo, always watching, perceives Geto as the one who left, symbolized by the black fish that swims past and away from him.

Gojo (top) watching the black fish.

Geto (bottom) ignoring the white fish.

Lacan's concept of the mirror stage is instructive. The self is formed not in isolation, but in recognition of the Other. Gojo and Geto, in this sense, are mirrors of each other—their identities forged in mutual recognition. When that recognition breaks, so does their coherence of self. Gojo continues to watch the fish; he never stops seeing Geto as part of himself. But Geto, unable to recognize himself in Gojo anymore, turns away.

Moreover, the scene with Geto pacing in the rain, anxious and ruminative, juxtaposed with Gojo arriving late, distracted by stray cats, dramatizes their differing temporalities. Geto lives in a timeline of existential urgency; Gojo in one of delayed awareness. When they finally meet again, Geto is distant but not entirely cold. The smile he gives is tired, but not devoid of affection. Their bond persists, even as ideology and identity diverge.

Quiet Love and Tragic Togetherness

The emotional current of their relationship could be read as a form of "quiet love" — not necessarily romantic in the conventional sense, but intimate, vulnerable, and full of suppressed emotional resonance. Freud's notion of ambivalence in mourning applies here: to mourn someone is to mourn part of oneself. Gojo never truly recovers from Geto's fall. It signifies that despite all ideological divergence, Gojo never ceased seeing Geto as someone worth saving, someone worth loving, even if that love could never be fully expressed or understood within the rigid frameworks of their world. Even at the end of Geto's life, Gojo cannot bring himself to follow through with the order to destroy his body. Instead, he hides it—a quiet act of defiance and devotion that speaks volumes. This gesture is not merely the refusal to obey protocol; it is reverence, memory, and a final, desperate attempt to preserve the person Geto once was. In Freud’s framework, mourning is an ambivalent process of letting go and holding on; Gojo cannot release Geto because doing so would mean severing a part of himself. The fact that he preserves Geto’s body, even knowing the risks, shows that for Gojo, Geto is not just a memory or a former friend—he is a fragment of Gojo’s own identity. The later violation of Geto’s corpse by Kenjaku is so horrifying to Gojo precisely because it desecrates that sacred memory. It is a literal and symbolic possession of Gojo’s past, weaponizing his grief against him.

Their togetherness was not just functional but existential. They were strongest together not merely in combat, but in spirit, in identity. Nietzsche writes that “in every real man a child is hidden that wants to play.” With Geto, Gojo could play—could be foolish, human, unguarded. And with Gojo, Geto could believe—believe in people, in goodness, in a reason to protect. Their bond suspended the brutal calculus of strength and weakness that defined the world around them. In each other, they found not escape, but relief. Their friendship was a space of freedom, a temporary shelter from the deterministic forces that would ultimately consume them. When that bond was severed, both were forced back into the cold machinery of ideology, duty, and isolation. Their separation marks not just the loss of a companion, but the end of a shared world—a private horizon that once made the unbearable bearable.

Among Heaven and Earth

Saturo Gojo during his awakening, quoting a phrase often attributed to the Buddha.

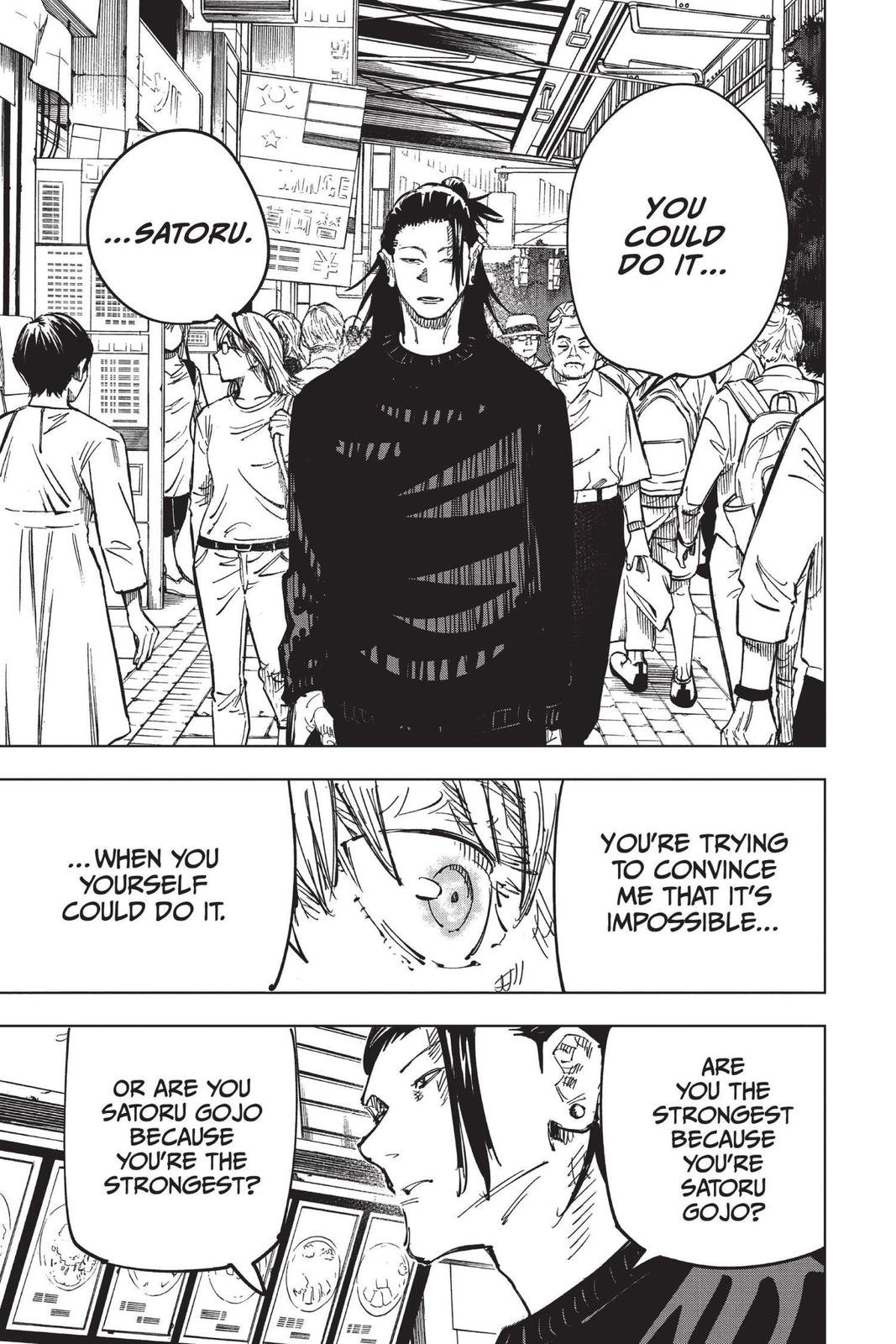

After Geto’s betrayal, one of the most psychologically wounding moments is not found in a battle or overt declaration of hostility, but in a single, cutting question: “Are you the strongest because you're Satoru Gojo, or are you Satoru Gojo because you're the strongest?” This line is far more than rhetorical. It’s a direct assault on Gojo’s existential foundation. Following his near-death experience during the failed Riko mission, Gojo experiences a Buddhist-like enlightenment—a moment of satori—declaring, “Among heaven and earth, I alone am the honored one.” This epiphany crystallizes his identity as the strongest, separating him from the limitations and moral burdens of others. In Lacanian terms, this moment could be interpreted as Gojo's attempt to stabilize the Symbolic order of his self through an Ideal Ego that can no longer be harmed, a transcendent subject beyond suffering. Geto’s question, then, becomes a strategic blow to that Symbolic identity, a destabilizing echo that challenges the coherence of Gojo’s self-understanding. It forces Gojo to confront whether his identity is grounded in essence (who he is) or in performance (what he can do).

Suguru Geto (top and bottom panel), speaking with Saturo Gojo (middle panel).

Moreover, Geto’s interrogation implies that Gojo’s strength might be an artificial construct, a mask concealing a fragile or hollow core. By framing the question in this way, Geto introduces a Kierkegaardian despair—the despair of not being oneself. If Gojo is only Gojo because he is the strongest, then his identity is contingent, not essential; it is a role propped up by power rather than a self freely chosen. This aligns with Nietzsche’s critique of identity built on reactive forces—strength defined by what it does to others, rather than an affirmative will to power. For Geto, who once believed in protecting the weak, this is a tragic irony: Gojo, who was once his equal, has become so consumed by strength that his very selfhood may be imprisoned by it. Thus, the question is not just accusatory—it’s surgical, exposing the fracture between Gojo’s divinized persona and the lonely, haunted man beneath it.

Their Fates Beyond the Grave

It is tragically poetic that Gojo, who once stood as the embodiment of autonomy and limitless power, is ultimately reduced to a mere tool—his body weaponized by Yuta in a desperate bid to destroy Sukuna. In mirroring Kenjaku’s technique, Yuta reenacts the same violation that once desecrated Geto: the act of turning a person, once beloved, into an instrument. The philosophical weight of this moment cannot be overstated. Martin Heidegger distinguishes between Zuhandenheit (ready-to-hand) and Vorhandenheit (present-at-hand), drawing attention to how beings are treated either as subjects or as mere utilities. Both Gojo and Geto, in death, are stripped of their Dasein—their lived, chosen being—and reclassified into the realm of tools. What was once relational, emotional, and human becomes functional. Their immense power, which once allowed them to act freely and shape the world around them, is ultimately exploited by others in a desperate attempt to assert control over chaos. Their bodies become objects—mere conduits for violence—emphasizing how even the most powerful are not immune to the cold reification imposed by war, ideology, and desperation.

Kenjaku in Geto’s body (left) introducing himself to Gojo (right).

This turn of events echoes Karl Marx’s theory of alienation, particularly the alienation from one's own essence and labor. In life, both Gojo and Geto acted according to personal conviction—however flawed, their actions were still grounded in meaning, loyalty, and identity. But in death, their identities are hijacked by others' intentions. Yuta may act from loyalty and love, but his use of Gojo's body echoes the utilitarian logic of Kenjaku and the wider jujutsu world, where strength is currency and personhood is secondary. The irony is devastating: Gojo, who once asked if he was the strongest because he was Satoru Gojo, or Satoru Gojo because he was the strongest, is reduced to neither. In the end, he is just strong—a force to be wielded. And like Geto before him, his body becomes the battlefield upon which others write their narratives. The existential horror lies in the realization that to the world around them, Gojo and Geto were never truly seen—only used.

Yuta, one of Gojo’s students, possessing Gojo’s deceased body.

Conclusion: Blue Still Lives There

Gojo and Geto are not merely foils; they are metaphysical complements. Their story is one of deep union and painful severance, of ideological mirroring and mutual misrecognition. Drawing from Kierkegaard’s notion of the self as a relation that relates itself to itself through another, we see that neither Gojo nor Geto can fully articulate who they are apart from the other. Gojo, the strongest, finds his power incomplete without someone to share the burden, someone to understand. Geto, the idealist turned nihilist, loses himself when the world breaks the values he once held sacred. Their tragedy is not simply that they end up on opposite sides of a moral war, but that the world could not sustain a space where their togetherness could flourish. The system they fought for, and later against, never had room for the intimacy they shared—an intimacy forged not just in battle, but in silence, trust, and shared vision.

It is within this frame that ἀγάπη—the truest, most enduring form of love—emerges. Unlike éros which seeks possession, or philia which depends on reciprocity, ἀγάπη gives even when nothing is returned. Kierkegaard calls it “the love that remains,” the kind of love that endures in loss, and perhaps even becomes most visible in it. Gojo cannot destroy Geto’s body; Geto, even in his final confrontation, cannot suppress the remnants of warmth that once defined them. This is not romantic idealism but existential realism: their love was never about victory, agreement, or even survival. It was a shared becoming—two selves formed through and for one another, even as fate tore them apart. Their strength, as Geto once saw it, was never in domination but in togetherness. With Gojo, Geto could believe. With Geto, Gojo could rest.

Even in death, the echo of this bond continues. Both are used—possessed, weaponized, and stripped of their dignity—by those who see only their power, not their personhood. That Yuta, in an act of desperation, must possess Gojo’s corpse using Kenjaku’s technique is not just poetic irony—it is tragedy intensified. The ones who bore the world’s weight are reduced to tools, their memories repurposed as tactics. And yet, this dehumanization only underscores what they were to each other: not weapons, not gods, but human beings who once shared a home in each other. Blue still lives there—not just as a color or a power, but as a place: the shared horizon of their youth, the gravitational center of their intertwined identities, and the ghost of a bond that, even in silence, continues to speak.

Thus, the relationship between Gojo and Geto—romantic or platonic—is a rare instance of ἀγάπη made visible in all its complexity. It is wounded and unresolved, yet it remains. Lacan might say their desire was for recognition, a mutual gaze in which each found himself mirrored. Heidegger would call it a being-with, a form of presence that transcends the ontic and shapes the very structure of their being. Nietzsche, in all his severity, gives us the image of eternal recurrence: would you live your life again, exactly the same? In their glances, in their silence, in their heartbreak, the answer feels like yes. They are strongest not because they conquered the world, but because they bore the unbearable—each other’s absence. Their love is not consummated, but it is consecrated. And in that, it becomes something rare: not a fleeting passion, but a sacred and tragic eternity.